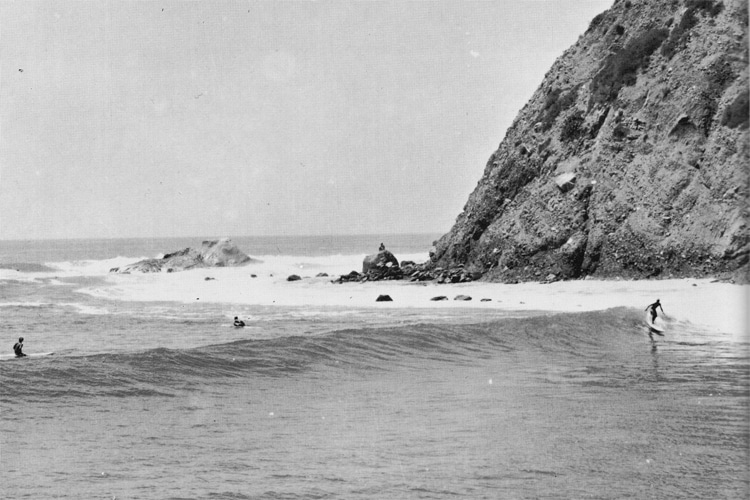

If you drove down Highway 101 in the 1950s and turned off at Dana Point, halfway between Laguna Beach and San Clemente, you’d find one of the most spectacular waves Southern California ever knew.

Locals called it Killer Dana, a right-hand point break that, when it lit up, could rival Malibu for consistency and Rincon for length.

The thing is, it packed way more punch.

Killer Dana was a cultural hub, a natural amphitheater where deep-water south swells reared up and wrapped around the rocky headland, peeling for hundreds of yards toward the pier and the sandy beach inside the cove.

Time and development put an end to it, like many other surf gems around the world.

A Wave With Power and Grace

What made Killer Dana special was the way it gathered energy from the open Pacific. Swells traveled up the coast, hit the point, and bent into perfect lines.

It was a dreamy, designer-like natural wave.

On smaller days, it was a fun, user-friendly break, with peaks inside the pier that beginners could ride for 200 yards.

On big days, though, Killer Dana turned serious.

Here’s how the “Surfing Guide to Southern California” by David H. Stein and William S. Cleary put it in 1963.

“Thick lines wind around the point and build up on outside reefs, with fast takeoff on larger swells (6 to 12-15 feet) developing into a slower, mushier, but often well-shaped lineup.”

The ride could stretch to 500 yards, connecting sections from the point past the pier.

But it was not without hazards.

Sharp rocks lined the takeoff zone, and at certain tides, a kelp-covered boulder created a nasty boil.

Boards were heavy, the surf was powerful, and getting caught inside could mean splintered wood and stitches.

The greedier surfers were, the more broken boards and bruises.

The wave’s reputation grew partly from its danger, hence the name “Killer Dana.”

The Surfers Who Owned It

From the 1930s to the 1960s, the point attracted a cast of characters who became legends. Lorrin “Whitey” Harrison, George “Peanuts” Larson, and Ron Drummond were among the first regulars.

Larson, in particular, earned mythic status when he allegedly rode one of the biggest waves ever attempted on the California coast in 1939.

By the early 1950s, a new generation was pushing the boundaries.

A 13-year-old Phil Edwards – yes, the Pipeline pioneer – made his mark at Killer Dana in 1953, showing off a new style of “hotdog” surfing while older riders stuck to cautious lines.

“He dropped all jaws with his silky fades and radical redirections,” recalled Surfline’s Greg Heller.

Edwards would go on to be hailed as one of the most influential surfers of all time, and Killer Dana was where he first turned heads.

Filmmaker Bruce Brown surfed here even before “The Endless Summer” hit the theaters.

So did Hobie Alter, who opened his surfboard shop nearby and helped launch the surf industry.

Corky Carroll, Bill Hamilton, and even visiting Hawaiian chargers like Jock Sutherland had their glorious moments on the wave.

Dana Point became not only a surf town but also an industry hub, with Surfer magazine founded just blocks away.

Dana Point Was a Surfing Community

Surfing was only part of the scene. Locals speared abalone, fished lobster, and spent entire days in the cove.

Dana Point was a small, tight-knit community of watermen.

As filmmaker Dustin Elm described it, “It was a true community of watermen, spending all of their time in Dana Cove.”

That sense of place made Killer Dana a lifestyle, a rhythm, a way of being tied to the ocean, which is why the next chapter still stings.

The Fight for Killer Dana

In the early 1960s, plans emerged to build a large marina at Dana Point. The project promised economic growth: boat slips, condos, shops, and tourism.

To city leaders, it was progress. To surfers, it was destruction.

Local legend Ron Drummond even tried to save the break, proposing an alternate harbor design that would leave the wave intact.

But surfers, still seen as troublemakers and dropouts, weren’t taken seriously.

Officials famously told them: “We don’t want those surfer vandals in our harbor.”

By 1965, the U.S. Congress had funded the project. In 1966, thousands of spectators cheered as the first boulders for the breakwater were dropped.

To surfers watching from the beach, it felt like a funeral.

On August 29, 1966, Killer Dana was surfed for the last time. Among the riders that day were “Peanuts” Larson and Ron Drummond.

Soon after, the cove was closed to “marine activities,” and construction crews got to work. Within two years, Dana Point Harbor stood where Killer Dana once broke.

A Whole Coastline Erased

The harbor killed Killer Dana, and bulldozed an entire surfing landscape.

Princess Point, Fisherman’s Reef, and several other breaks vanished under concrete and rubble.

The famous headland itself was leveled, and an important part of surf culture was erased and vanished from the California surf map.

When asked about the wave in 1967, the always-contrarian Miki Dora downplayed its danger.

“The only ones I’ve ever heard of being killed there were a couple of over-anxious Valley kooks who slipped on a banana peel,” he said.

But to most surfers, Killer Dana’s demise was no joke.

It was the first major break lost to coastal development and became a rallying cry for a movement that would later give rise to groups like the Surfrider Foundation.

What’s Left Today

Dana Point Harbor now holds yachts, restaurants, and parking lots. Doheny, the soft longboard wave nearby, is all that remains for surfers.

A time capsule hidden inside the first harbor boulder contained a photo of Killer Dana locals preparing for one of their last sessions, their faces grim.

It was set to be opened in 2016, precisely 50 years after the point break’s death.

Matt Warshaw later wrote in “The History of Surfing,” “Surfing environmentalists long waved the bloody flag of Killer Dana, a beautiful headland-fronted Orange County point wave buried in 1967 beneath the new Dana Point Harbor.”

The flag still flies.

For older surfers, Killer Dana lives on in stories of peeling rights, giant hurricane swells, and the day Southern California lost a crown jewel of surfing.

Hopefully, the few that still exist will survive the thing we all, on terra firma, call “progress.”

Words by Luís MP | Founder of SurferToday.com

Leave a Reply